So you have successfully resolved your problem with the help of a psychotherapist or perhaps you found some alternative way of solving your problem. Good, you are on the right track but did you think about the possible relapse and how to prevent it? Relapse is as setback after a period of improvement, which can prevent your from completely resolving your problem.

If you want to become independent of the therapist, and be able to use coping techniques and strategies in different situations on your own, you must learn how to deal with a possible setback. If you are one of those people who has almost resolved a very serious psychological, emotional or a behavioural problem and you anticipate that you might completely prevent relapse, you might be disappointed. However, this doesn’t mean that you can’t do anything about it. What you can do, is learn how to cope with a relapse and regain progress that has been lost.

Photo by kean kelly

Relapse management begins by asking yourself the following questions after a setback:

- How can I make sense of this?

- What have I learned from it?

- Now that I know this, what would I do differently?

By reflecting back on your setbacks, you can turn them into learning opportunities and become stronger than you were before. “If you strike me down, I shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine.” – Obi-Wan Kenobi

Here is a short story about how Carol dealt with her eating disorder relapse¹

Carol struggled with an eating disorder and had periods of binge-eating. One evening she bought quite large quantities of her favourite foods, went home alone and consumed it, only spitting out chewed mouthfuls when she became over-full, but unable to stop eating. During this time she could not stop herself. Such an evening would usually have marked the beginning of a significant decline.

She would have woken the next day feeling physically unwell and uncomfortable, she would have concluded that she was a hopeless failure and her mood would certainly have been depressed. As a ‘hopeless failure’ she would have felt powerless to resist the urge to comfort eat. However, on this occasion, she asked herself: How can I make sense of this lapse?

She realised that she had been feeling stressed at work for several days but had kept pushing herself in order not to think about her troubled relationship. In addition, she had begun to resume her old habit of starving throughout the day in an attempt to lose weight.

Once she had reflected on her situation, she was then able to say: ‘It’s no wonder that I fell off the wagon. Not only was I stressed to breaking point but I set myself up for a binge by not eating during the day.’ What have I learnt from it? ‘I realise that, for me, it is dangerous to starve as a means of weight control – it backfires. Also, I need to keep a check on my stress level: when it gets too high I am vulnerable to comfort eating.’

With hindsight, what would I do differently? ‘Hard as it is, I would try to eat “sensibly” and avoid starving. Looking back, I made a mistake in trying to pretend that I did not have problems in my relationship and then throwing myself into my work as a distraction. If I had that time over again I would acknowledge my problems, or maybe even talk to someone about them rather than ignoring them.’

By reflecting back on her setback and thinking creatively, Carol created a plan for coping with similar problems in the future. She has also gained an insight about her needs and weak spots. By reframing setbacks into learning opportunities, Carol will continue to improve her understanding of challenges and develop better coping skills.

Relapse Vulnerability Factors

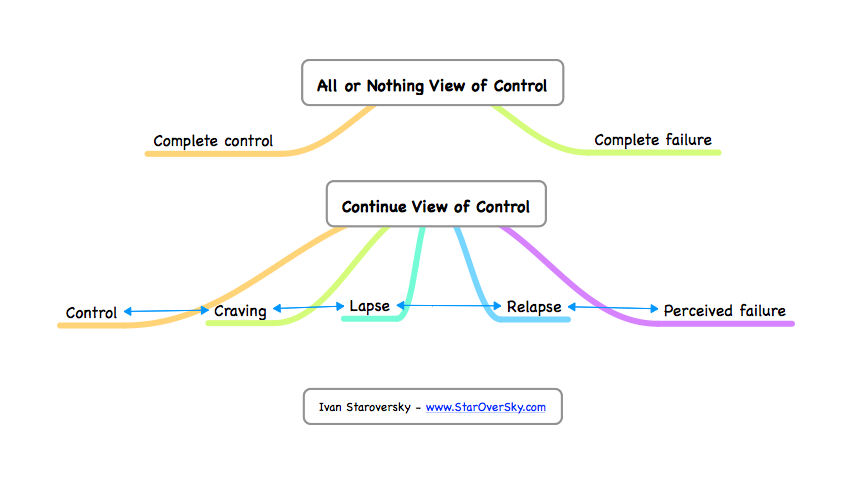

All or nothing interpretation of a setback

People with black and white thinking style or those who have thought about themselves as either being in control or having failed tend to relapse the most at the first sign of challenges. These people often switch from feeling in control to feeling as if they had a complete failure. Once they get sucked into the failure mindset, they tend to increase their sense of hopelessness, which further increases poor behaviours such as continuing drinking to feel better.

A better approach is to develop a more flexible attitude of being in control and slipping out of control. This kind of attitude allows small and even big setbacks to be experienced without automatically jumping to a conclusion of failure.

Click the image to enlarge

Adapting a more flexible model of control and perceived failure can help you perceive a setback as temporary change in the course of direction which could be corrected. To develop better flexibility in your attitude and behaviour regarding setbacks, ask yourself these questions:

- When will I be at risk of this happening?

- What are the signs?

- What could I do to avoid losing control?

- What could I do if I did lose control?

- What is the worst thing that could happen?

- What can I do to prevent it or deal with it?

If you can come up with answers to these questions, you’ll be able to recognize the early warning signs and try to avoid a potential setback as well as have a back-up plan in case of failure. Thus, you can think of a lapse (temporary failure) as an anticipated event for which you already have a solution(s).

How To Deal With a Relapse

It is highly recommended that you write down your personal plan for minimizing relapse and have easy access to it. You can use your smartphone or daily journal to remind you that you have a relapse management solution in your pocket.

Being in a high-risk situation

People who are depressed, socially isolated, or those who have an eating disorder and do not eat for too long have a higher likelihood of relapse. By observing your own thoughts and behaviours you can predict and avoid high-risk situations.

If you have a depression and you notice that you can become miserable when you are socially isolated, you need to focus on how you can maintain social contacts. If you have an eating disorder and are at risk of binge-eating when you are stressed out or hungry, you need to think of how you can avoid getting into these kind of situations.

However, life tends to be very unpredictable and sometimes difficulties are unavoidable and you may find yourself in a high-risk situation. But this does not mean that you cannot prevent or manage relapse. Make sure that you have a good set of coping skills and that you haven’t grown increasingly ambivalent about change and if you did, this can be fixed by reseting your motivation to change.

Having poor or no coping strategies

Poor mood coping skills or no helpful techniques for dealing with hunger pangs in a controlled way can cause you to feel vulnerable when you have to deal with a challenge. Developing proper resourceful cognitive and behavioural coping strategies and planning how you will put them into action are strongly recommended.

If you have already developed a set of coping skills, it is a good idea to keep reminders of what works for you and be able to access these reminders whenever there is a need. You can use your smartphone to write down what works for you and open this note if you’ll have a hard time remembering what to do when you are dealign with a problem.

For example, if you have experienced depression, you might want to write down a list of all the social activities and people that you could contact if you feel vulnerable. If you have a problem with binge-eating, you can write down specific activities that decrease or defuse your urge to binge.

The sense of loss of self-efficacy

Thoughts such as: ‘I’m hopeless, It’s my fault that I’m depressed, there’s no point in trying to resist, or I just can’t, give people the permission to fail or give in. This type of thinking can be further increased if a person abuses substances such as drugs or alcohol.

To cope with this problem, you can create hopeful and empowered self-statements. For example: ‘It is my way of thinking that is bringing me down, but as hard as it is, I can train myself out of it again. I have lots of friends who want to support me. I can resist this temptation just like I have resisted in the past. It may not be easy for me to do this but I know that it’s possible and good for me. I can do it!’

Anticipating when you are likely to use such statements is important. You can rehearse through role playing or imagination. Remember to focus on self-compassion rather than unhelpfully bullying or critical self-statements.

Engaging in unhelpful behaviours

Withdrawing further from social activity or binge-eating are example of unhelpful behaviours. Sometimes people can get stock in a powerful and unhelpful cognitive–behavioural cycle. You can use cognitive restructuring to break the pattern and to support a positive behavioural change.

Note that the more ambivalent you are the more difficult it might be to create resourceful statements. Ambivalence about change can prevent you from making positive changes and lead to even more vulnerability, lapses and relapse. Having a strong motivation to change is essential to making sure that can achieve positive and long-lasting results.

Abstinence Violation Effect (AVE)

Abstinence Violation Effect is a psychological state in which a person is unable to break away from the problem behaviours because they only focus on negative thoughts. To deal with AVE, it is possible to identify the steps that can lead to AVE and interrupt the progress towards relapse using a specific technique or method.

Reference:

Westbrook, D. E., Kennerley, H., & Kirk, J. (2011). An introduction to cognitive behaviour therapy: skills and applications (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Credit (CC4): staroversky.com/blog/how-to-deal-with-a-relapse-and-get-back-on-track-after-a-setback